W. E. B. Du Bois

|

|

Connections

|

W.E.B. Du Bois was born in the village of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, three years after the end of the Civil War. Unlike most black Americans, his family had not just emerged from slavery. His great-grandfather had fought in the American Revolution, and the Burghardts had been an accepted part of the community for generations.

W.E.B. Du Bois was born in the village of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, three years after the end of the Civil War. Unlike most black Americans, his family had not just emerged from slavery. His great-grandfather had fought in the American Revolution, and the Burghardts had been an accepted part of the community for generations.

Yet Du Bois was aware of differences that set him apart from his Yankee neighbors. In addition to the austere hymns of his village Congregational Church, Du Bois learned the songs of a much more ancient tradition from his grandmother. He realized that this earlier tradition set him apart from his New England community and the chronicle of Western Civilization that he learned at school. Du Bois excelled at school and outshone his white contemporaries. While in high school he worked as a correspondent for New York newspapers.

Meanwhile he started to notice the subtle social boundaries which he was expected to observe and became determined that the community would recognize his academic achievements. Du Bois had always wanted to go to Harvard; he was initially disappointed when he learned that influential (white) leaders of his community had arranged for him to attend Fisk University in Nashville. But the experience changed his life. It helped to clarify his identity and pointed him in the direction of his life’s work. He was determined to continue his education, and his perseverance was rewarded when he was offered a scholarship to study at Harvard University.

Du Bois’ life was a struggle of warring ideas and ideals. He entered Harvard during its golden age and studied with William James and Albert Bushnell Hart. Du Bois was smitten with the ideal of science – that an objective truth that could dispel the irrational prejudices and ignorance that stood in the way of a just social order. At Atlanta University he created landmarks in the scientific study of race relations.

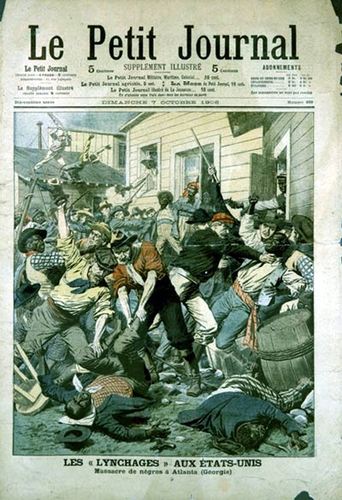

Yet a shadow fell over his work as he saw the nation retreating into barbarism. Du Bois’ faith in the detached role of the scientist was shaken, as he saw the increase of repressive segregation laws, lynching, and terror. After the Atlanta Riot of 1906 Du Bois’ “Litany at Atlanta” passionately sounded a challenge to those forces of destruction. Bois sounded a call to arms with the founding of the Niagara Movement and later the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He became an impassioned opponent of the legal, political, and economic system that thrived on the exploitation of the poor and the powerless.

As he pointed out the connections between the plight of Afro-Americans and those who suffered under colonial rule in other areas of the world, his struggle assumed international proportions. The Pan-African Movement that flowered in the years after World War I was the beginning of the creation of a third world consciousness. As he became more of an international figure, Du Bois was accepted less and less by his contemporaries at home. Yet when he left the United States to become a citizen of Ghana in 1961, he did not see it as a rejection of his countrymen. Returning to the land of his forefathers marked a resolution of many conflicts with which Du Bois had struggled all his life.

Du Bois’ last statement to the world was one of hope and confidence in the ability of human beings to shape their own destinies. “One thing alone I charge you,” he wrote,“As you live, believe in Life! Always human beings will live and progress to greater, broader and fuller life. The only possible death is to lose belief in this truth simply because the Great End comes slowly, because time is long.”

─—adapted from a biography by Kerry W. Buckley, Special Collections & University Archives, University Libraries, UMass Amherst; image courtesty of Special Collections & University Archives |

|

Dating from 1961, this New York Times article states that Du Bois officially joined the Communist Party at the age of 93. Du Bois had long been accused by the government of supporting Communism, but he did not join the organization until the US Supreme Court upheld a law (FARA) requiring all communists to register with the government.

|

|

Here you will find the application letter from Du Bois to Gus Hall, leader of the CPUSA, asking to join the Communist Party, as well as the acceptance letter from Hall officially welcoming Du Bois into the Communist Party USA.

|

|

In 1906, riots broke out in Atlanta, spurred by a gubernatorial campaign and allegations of blacks attacking white women. Thousands of whites marched through town, attacking blacks. In response to the attacks, Du Bois wrote a poem called “The Litany of Atlanta.”

|

|

“W. E. B. Du Bois and the Atlanta University Studies on the Negro” by Elliot Rudwick discusses Du Bois’s time in Atlanta, where he oversaw a social study at Atlanta University, a traditionally black college.

|

“The Litany of Atlanta” by W.E.B. Du Bois, written following the Atlanta Riots of 1906

|

|

This is the extremely influential text of The Souls of Black Folks, used by many of the artists in the exhibition.

|

The FBI kept a file on Du Bois that catalogued his travels to Germany, China, and Russia, as well as his various works and speeches, because they believed he was a Communist and potential threat.

|

|

The Peace Information Center was indicted under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) in 1951. The act required “foreign agents” to register, because the government was trying to curtail communism and war in the US. This is the indictment that lead to Du Bois joining the CPUSA.

|

Du Bois and the NAACP founded of The Crisis in 1910 as a journal for thoughts and opinions on civil rights, culture, art, and politics. Many of Du Bois’s famous essays were published in The Crisis. The magazine is still an active publication with many of its issues available online.

|

|

A telegram from Albert Einstein and other requesting Du Bois presence at a meeting about the preservation of peace in the light of nuclear weapons.

|

Du Bois received his PhD from Harvard University in 1895, writing his dissertation on the trans-Atlantic slave trade. See Artist Mary Evans for more Information.

|

|

“The Talented Tenth” is chapter from a book he co-wrote with Booker T. Washington. In the chapter, he talks about the high education of blacks, what the current system does, and how it needs to change.

|

The Niagara Movement was a civil rights group founded by Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter, and is often seen as the precursor to the NAACP. This image is a list of the principles of the Niagara Movement, stating for what it stands.

|

|

The Quest of the Silver Fleece is a novel by Du Bois. It came after years of Academic writing, dealing with the same issues of race and identity as his other works but in a fictional format.

|

For The American Negro Academy, “The Conservation of Races” concludes with a list of goals and beliefs that Du Bois wishes to impart on the Academy, including a belief that whites and blacks can exist in harmony and in mutual happiness.

|