James Gehrt

The Weight of Air

The Weight of Air is a cross-disciplinary, multi-media exhibition by photographer, videographer, and imaging specialist James Gehrt.

September 11 – October 6, 2016

Opening Reception: Sunday, September 18, 2-4 p.m.

Original score performed live by John Nolan* during the reception on Sunday, September 18, between 2 PM and 4 PMLight and Air

An Exhibition Essay

by Anthony W. Lee**

Photographers usually talk about light. Seeing it properly, wrestling with it, corralling enough of it—maybe just enough—with the camera’s aperture, shutter, and film speed (or, these days, the digital sensor’s ISO), these are among the most important aspects of skilled camerawork. Too much light, and the picture is overexposed and the subject blown out; not enough, and the whole thing is a murky morass. Whereas some photographers regard the handling of light as one part of the process of picture-making, a necessary prelude to getting the subject right, James Gehrt focuses on the play of light itself as a subject. Take his Hallway Door, in which the light sneaks around the rails and stiles of an old door and cantilevers off the floor and baseboards of a dark hallway. Or take Hotel Curtains, in which the light filters through the warp and weft of curtain fabric and bounces softly across a windowsill. In these photographs, light is the principle actor; its movement in, around, and through various spaces provides the central interests. Indeed, the hallway is otherwise empty and the hotel window unobservant.

Or take another photograph, Puddle Jump Reflection, which may summon to mind a famous photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson called Behind the Gare St. Lazare from 1932. The two photographs share an interest in the shadowy reflection of a figure jumping over a wet slice of land. But whereas Cartier-Bresson’s photograph asks us to attend to the overall design of elements that the jumping figure has brought in its wake—the jigsaw-like rooflines above, the rhythm of iron bars in the middle, the circles and semi-circles below, the whole of which, in their serendipitous arrangement before the camera, Cartier-Bresson would later call a “decisive moment”—Gehrt’s asks us instead to see the shadow as a jagged interruption of darkness on light. In this sense, in his photograph it is less a serendipitous or decisive moment that we encounter but rather an exactingly observed one. And it is not just pool of water that we see below but in addition a pool of light.

What does it mean to photograph light? Strictly speaking, one does not readily “see” light but instead its effects on the objects of the world. We spy a lily pad in a frozen pond, for example, and we are likely to say to ourselves, “yes, that’s a lily,” without thinking too much about how the action of light has brought the lily into our purview. It’s as if the lily exudes light as opposed to absorbing or reflecting it. But Gehrt photographs in such a way, as in his Frozen Lily, that we also want to say to ourselves, “yes, that’s a lily whose petals have been illuminated in a striking way.” In such a picture, we note a darkness at the edges of things, a certain rumpled quality to the surfaces, an undulation of grey tones across the petals and sepals. That’s to say, the workings of light very much matters in our regard of the subject. Light acts, the curious materials of the world are revealed, the fineness of things emerges, and other details fade away. Most of all, we are aware that an observant eye has made note of the activity and used a camera to lay claim to it.

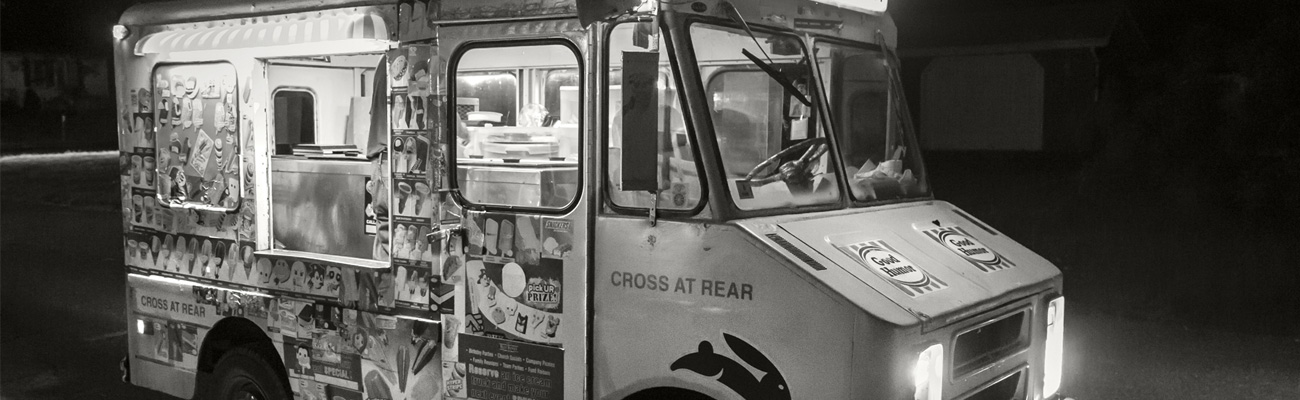

Gehrt makes a habit of venturing out to the streets when photographing light is not only the chief concern but also the most challenging. The early morning appears regularly in his pictures, as do the dusky hours of early evening and black hours of night. He frequently shoots indoors, where the light can thin, become wispy and more harshly directional. He shoots through glass, where reflections and refractions come into play. He likes heavy shadows, where light is blocked and we are left with graphic-like voids. He confronts neon signs, headlights, and fluorescent tubes in the inky darkness. Can he control the light in those instances, their blaring, flashing, and insistent qualities?

There is something solemn, perhaps even a bit melancholic about Gehrt’s photographs. On the one hand, this effect is the result of how light brings about a certain formality to the objects it reveals. Light becomes, in the pictures, a “stilling” agent, by which I mean that it has a way of turning the objects of the world, no matter their differences from each other or how the photographer in his wanderings has come upon them, into still lifes. As in still life painting, the objects are revealed as both poignant and preserved; and there is a hushed quality that surrounds them. On the other hand, this solemn effect is also the result of the original commonness and simplicity of the objects and their being made, by the action of light, into something venerated. In Gehrt’s pictures, the everyday has a certain grace to it, not in a religious sense but rather an aesthetic one. The world can achieve a level of quiet enchantment, even some dignity, the photographs seem to say, if we observe how light acts on its daily particulars.

I think this is what Gehrt means when he says “air” or the “weight of air.” As with light, we do not readily see air, but of course we would easily note its absence, not so much by what we do or do not see but by how we feel. Not enough air and our lungs seize, our breathing becomes frantic and halting, we gasp and heave and begin to lose control of our senses, the world begins to disappear. That’s to say, we require air but hardly think about it, unless it grows thin or is absent. Breathe deeply, Gehrt’s photographs also seem to say, and, quite the opposite of a condition of seizure or franticness because of a lack of air, feel instead a state of rightness or, better yet, of heightened lucidity, of pure air.

The “weight of air,” the quality or condition of “rightness,” the sense of a heightened “lucidity”—of course we are in the realms of metaphor and analogy here. In the history of photography, there have been many such attempts to put into words the visual quality of a photographic sensibility. The one, for me, that comes closest to mind was an account by Alfred Stieglitz about how he came to photograph one of his most famous pictures, The Steerage, of 1907. Stieglitz was traveling on an ocean liner with his wife and some of her insufferable companions. To escape their company, he wandered above deck and came to a place where he could see a crowd of poorer passengers, most of whom were crammed into the lower deck, or steerage, of the ship. He viewed the crowd, the clothes of the men and women, a straw hat on one of the men, white suspenders on another, the stairway leading between decks, and more. “I stood spellbound for a while,” he wrote, “looking and looking.” What did he see? It was just a crowd of commoners, true, but it was also more. “I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that the feeling I had about life . . . people, the common people, the feeling of the ship and ocean and sky and the feeling of release.” There was something right about the scene. Standing on the deck, camera in hand, with a recognition that he had escaped the suffocating company of the nouveau riche and entered into a new terrain of . . . what? A state of photographic grace? He could not name it more precisely than a “picture of shapes.” The shapes fell into order and spoke to his sense of his life at that moment; and he had clear-eyed view, a heightened understanding, of what they meant to him. Could the camera capture it? “Would I get what I saw, what I felt?” he asked. “Finally I released the shutter. My heart thumping. I had never heard my heart thumping before. Had I gotten my picture?”

Yes, Stieglitz, you might have. How may we judge? See the light. Breathe the air.

James Gehrt Bio

James Gehrt is a fine art photographer and imaging specialist residing in Western Massachusetts. After receiving his BFA in photography from the Savannah College of Art and Design in 1991, his career began by assisting and printing for commercial and fine art photographers. Gehrt established a reputation for excellent print quality and technical proficiency which lead him to the position as the Lab Manager at the Chicago Albumen Works, in Housatonic Massachusetts. While at CAW for Seven years, he had the opportunity to work with some of photography's most important creators, including Walker Evans, Carlton Watkins, and Lazlo Maholy Nagy, to name a few. He also worked with collections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Archives, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Museum of the City of New York, and the Met Opera.

In 2007 Gehrt began as the Digitization Coordinator at the Mount Holyoke College Library. He has been awarded a 2009 and 2010 NITLE Technology Fellow, concentrating on new digitization technologies. His workshops in digitization best practices have been taught at the New England Archivists annual conference, Simmons College Continuing Education, NITLE, and the METRO Library Group in New York City.In 2014, Gehrt received his MLIS from Simmons College. He was honored with the Dr. Esstelle Jussim award in Photographic Studies. Gehrt was selected as Digital Project Lead at Mount Holyoke College in 2015.

Through it all Gehrt continues to carry a camera with him wherever he goes. Building a collection of thousands of images from everyday life that document the objects and locations he visits. Gehrt has produced seven self-published titles over the past eight years. This past summer his book "Source" was acquired by the Smith College, Mortimer Rare Book Room.

John Nolan Bio*

John Nolan is a Boston-area musician and educator. He received his Bachelor's Degree in Film Scoring from Berklee College of Music and his Masters in Music Composition from UMass Amherst. He writes and performs around the Boston-area and is currently on the faculty at Fitchburg State University and UMass Amherst.

Anthony Lee**

Idella Plimpton Kendall Professor of Art History at Mount Holyoke College Specialization Modern and contemporary European and American art; history of photography

Anthony W. Lee is an art historian, critic, curator, and photographer.

As a critic and scholar, he writes about American photography and modernist painting in the period between 1860 and 1960. As a photographer, he documents ethnic and immigrant communities. Lee teaches a series of lecture courses on art since the French Revolution and seminars on photography before and after World War II. Many of his seminars have resulted in exhibitions curated by students.

Lee is the recipient of the Charles C. Eldredge Prize for Distinguished Scholarship in American Art, given by the Smithsonian's National Museum of American Art, and the Cultural Studies Book Prize, given by the Association of Asian American Studies. He is founder and editor of the acclaimed series Defining Moments in American Photography.

Sponsor

More Information

Hampden Gallery Hours:

Hampden Pop-up Gallery hours:

Monday: 1:30 p.m. - 6:00 p.m.

Tuesday:1:30 p.m. - 6:00 p.m.

Wednesday: 4:30 p.m. - 7:00 p.m.

Thursday: 12:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m.

Friday: 12:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m.

*Follows the University's holiday schedule

Contact Information:

Main Number: (413) 545-0680

Gallery Director, Anne LaPrade Seuthe

Gallery Manager, Sally Curcio

Hampden Gallery

Hampden Gallery